By Dr. Joseph Chuman

In the circles I travel, it’s not uncommon for someone to invoke a writer or a thinker who has greatly influenced him or her. More unusual is for someone to invoke a single figure who has shaped one’s world view and life. I am one such person.

As I have mentioned frequently, this year marks a half-century since I began my professional career in Ethical Culture. It’s a benchmark that prods me to look back and try to take in the wider scope of my life.

My adolescence was not a happy one. My mother died when I was 12 and my father, who was always remote, fell ill and deteriorated physically, emotionally, and mentally. Like many children for whom the parental pillars of love and support are absent, I was forced to forge my own way in life from an early age, to pull myself up by my bootstraps, to invoke the cliché. And without much positive foundational support, I had to find and construct my own. Like many children in such circumstances, and given my background, I focused my energies on school and intellectual work. I buried myself in books, often very big books. I read “Moby Dick,” Victorian adventure novels, and there was heavy stuff such as “The Divine Comedy” and Dostoyevsky.

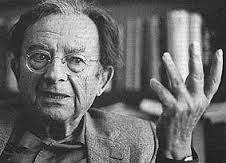

In my intellectual quests at the age of 16, just as I was entering college, I discovered the social psychologist Erich Fromm and proceeded to ravenously devour every book he wrote for the general public. Given my social isolation, my need to find a handle to leverage myself out of my unhappiness, as well as my skepticism of traditional religious belief, Erich Fromm’s philosophical psychology powerfully spoke to me and was a source of hope.

Fromm was explicitly a humanist, who put forward a philosophy of human fulfillment and happiness that I found captivating—and still do. Fromm wrote in an accessible style that was easy to engage.

His fundamental view, which can be traced back to Aristotle, is that human fulfillment is not an achievement but a process, namely the process of productively developing—the word he often used was “unfolding”—one’s potentialities. We all possess potentials—intellectual, emotional, physical, social, and so forth, and to the extent that we develop them, we become who we are and find fulfillment. Fromm’s is a philosophy of human flourishing. It commends action and not passivity. And it personally prompted me to set goals that I would use as levers in the development of my interests and talents. But another dimension of his thought is that we are not separate egos. We are social beings and the development of our potentials is something that we can do only in our relations with others. It is an aspect of humanism that I built on and deepened through the ensuing years.

And then there was his philosophy of work, which lies at the center of his notion of fulfillment and the development of our potentials. Here he borrowed from a humanistic interpretation of Karl Marx. Work, for Marx, is the way in which we use our powers to mold the outside world. And as we invest ourselves in molding the world, we dialectically create ourselves. In short, the ultimate purpose of work is to build our characters. In briefest terms, we become what we do. I likewise was captivated by this idea, implying that the purpose of work, in the final analysis, is not to make money or even to make a living but to become who we are.

Taking this humanistic philosophy and world view to heart, I sought out a life vocation that would be most faithful to it, and so I discovered Ethical Culture as an expression of Fromm’s humanism, and decided to dedicate myself to Ethical leadership as a fulfillment of his philosophy of work. I can think of no line of work that is a more faithful instantiation of his thought. I am an Ethical Culture leader because of the Erich Fromm philosophy that I imbibed when I was 16—and I have no regrets.

True enough, as my intellectual horizons have broadened, I have not remained uncritical of Fromm’s thought. In some ways, it is simplistic and there is an implicit moralism in holding up his humanistic ideal of human flourishing in that he does not give much credit to the human being in his flawed state.

Beyond personal psychology, Fromm’s most significant contribution was in providing an explanation for the emergence of fascism and the appeal of authoritarianism as an “escape from freedom,” as he so compellingly wrote. In this regard, Erich Fromm’s ideas retain their relevance to our current moment.

I plan to develop these notions, both personal and political, in my address of Dec. 1, which I have entitled, “The Thinker Who Inspired Me Most and His Relevance for Today.” May you all have a very pleasant Thanksgiving!

Dr. Joseph Chuman is leader of the Ethical Culture Society of Bergen County.