By Dr. Joseph Chuman

“All things flow” said the Greek philosopher Heraclitus. All things of this world—ideologies, social movements, artifacts constructed by man, living things, and we, too, are born, grow, decay, and disappear. We cling to what we have and what we love, but nature and time will have the last word.

In this regard I am thinking of our Ethical Culture Movement. Will it last? And if so, for how long before it, too, is swallowed by the inexorable flow of time? And more to the point, should it?

I have often observed that Ethical Culture is the only “religion of humanity” that was created in the 19th century that has survived into the 21st. Ethical Culture was very much a creature of its time and place, though when Felix Adler brought it into being in 1876, it was something new, and in the world of religion, something radical, as well. Here was a religious movement dedicated exclusively to ethical ideals without the salient characteristics possessed by religion for thousands of years: No God, no holy scriptures, no sacred figures, no dogmas, no required doctrines, no religious practices such as prayer, and no manifestations that set the religious adherent apart from his or her secular counterpart; in other words, no dietary prohibitions, no specific mode of dress, no specifically religious habits. Just ethics, pure and simple.

It was easier for Ethical Culture to make its mark back then, and despite its small size, it did. And it was able to attract the rich and the famous, as well. Part of this stemmed from Adler’s brilliance. When he spoke at Carnegie Hall, where the New York Society met before constructing its building in 1910, thousands came out to hear what the young mind was thinking. But Ethical Culture also thrived, as implied, because of its uniqueness. Though, as noted, it was a creature of its time, there was nothing quite like it, and for many for whom supernatural religion was no longer compelling, Ethical Culture was very attractive.

In earlier times, religious organizations provided social services

That was then, but what about now? Times have changed and not in ways that ensure the endurance of Ethical Culture. Since the New Deal, government has taken on many of the social services that in earlier times were left to religious organizations, such as Ethical Culture, to perform. And since social reform and social service have been mainstays of Ethical Culture, its profile in society was then more outstanding. Moreover, today such humanitarian work is undertaken by countless thousands of non-profit organizations, many with highly specialized mandates that attract large numbers of supporters to a huge range of causes. At one time, especially with a financially very well endowed membership that we no longer attract, we could be a leader in the arena of social change. Today, it is much harder to make our mark in a much more crowded environment.

On the philosophical side, our uniqueness as a religion dedicated exclusively to ethics has not utterly disappeared, but it has faded. As more people attend college and are schooled in the humanities, they absorb values that in many ways correspond to the world-view that Ethical Culture espouses. This is also true of liberalism that is conveyed through politics and the political culture. In the past 40 years, American society has experienced a wave of very conservative religion. But we can see this as a backlash against an increasingly secular and scientifically based culture, which is expressive, again, of the worldview that Ethical Culture represents. And in even more recent decades, we have seen a historical reversal in American religious life. Now, up to 25 percent of the American populace claim no religious affiliation. And within that trend there has been an interesting emergence of humanistic, free-thinking, and atheist organizations attempting to fill the space left in the wake of the retreat of formal religion. These groups are not quite Ethical Culture, but they are kissing cousins, and again, tend to diminish our appeal, and ostensibly our relevance in the wider world.

Where is our relevance now?

So, assuming our endurance rests upon appealing to interests and meeting needs that others do not, we can ask: Where is our relevance to be found in our modern times?

I have an answer to that question, which I will elaborate on in my address of Nov. 3, entitled “The Enduring Relevance of Ethical Culture.” I hope you can join me then.

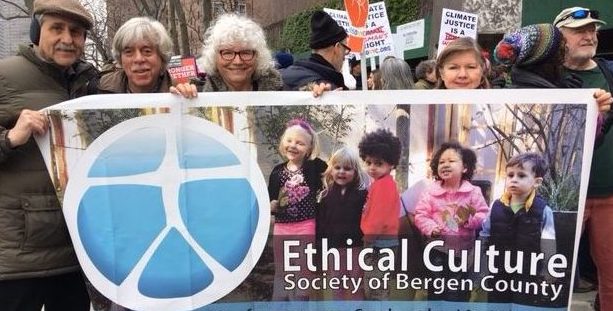

Dr. Joseph Chuman is leader of the Ethical Culture Society of Bergen County.