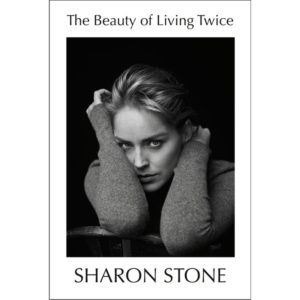

Review of The Beauty of Living Twice, by Sharon Stone (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2021)

By Theresa Forsman

If you, like me, generally do not read celebrity memoirs, especially Hollywood celebrity memoirs, you may want to make an exception for The Beauty of Living Twice, by Sharon Stone.

In telling her story, Stone, best-known as the sexpot serial killer in the 1992 movie Basic Instinct, demonstrates her intelligence, empathy, and stamina. Before recovering from a deep cut across her neck from an accident at age 14, before enduring the “casting couch” attitude of the show business industry decades before the #metoo movement, before overcoming long odds to pull through a severely disabling stroke at age 43, Stone survived childhood sexual abuse. Physical abuse, too. Her story is not the sad tale of a victim and this reader found few spots of self-pity. What’s remarkable about Stone’s story, what makes it worth reading, is that she shows a way of carrying trauma so that it doesn’t derail the rest of life. She demonstrates that with time and telling, the shame, fear, and anger so common to abused children can be stared down and put in its place.

Insight and compassion

Her memoir shows she has always been strong and courageous, but it’s unlikely that Stone, now 63, as a younger woman could have brought the level of insight and compassion that she does here to her story.

The second of four children, Stone grew up in poverty in Meadville, Pennsylvania, a town on the Erie-Lackawanna line “where hookers and heroin and everything bad got dropped off and no one looked back.” At school, she had trouble fitting in for several reasons, one being her exceptional intelligence, which turned out to be her getaway car. She recounts some of the cruelty she endured at the hands of classmates. “But I had smarts and I had style. Style is what you do with what’s wrong with you.”

As she accumulated life experience and more information about her parents’ growing-up years, Stone was able to bestow forgiveness and compassion on the father who had sometimes beat her with a belt, on the cold mother who had slapped her and broken a hairbrush over her head. Her parents, she came to know, “were both shipwrecked when they met. Neither of them had proper parents, nor homes, nor care, nor providence of any kind…”

With her grandfather, no such forgiveness was warranted. When Stone was 8, she witnessed him sexually assault her 5-year-old sister as her grandmother blocked the room’s exit. They kept the secret, under threat of death, even after he died. Once he was gone, “his threats were then null, I had things I finally could have said. Things that I wouldn’t be killed over. I, as a fourteen-year-old country girl, didn’t get this on a conscious level. That, I think, would have been far too overwhelming. I kept silent. But that season has passed. Now I’m telling you.”

The rage she carried for decades is what she tapped into to play the unhinged killer in Basic Instinct, a rage that frightened her at the time but was “incredibly freeing” to express.

Something in common with soldiers

The second life in the book title is Stone’s post-stroke life, in which she carries an insight that she says is unique to those who have been near death and survived. The bankable movie star had lost her health, her money, her career trajectory. “I don’t miss her,” Stone writes. “It’s like she is a person I knew very intimately, but not me. …I imagine that most people who survive extreme life-and-death circumstances feel this way. I speak with soldiers easily about this.”

Because of the circles Stone has moved in, her book includes several references to famous people, mostly in show business. She’s not name-dropping; she’s telling us what co-workers taught her, good or bad, how they shaped her view of not only the movie industry, but of humanity.

We learn of her two short marriages and her 20-year relationship with Robert Wagner, of her three adopted sons and her long custody fight for one of them, of her work with charities that fight HIV/AIDS and homelessness.

Stone’s acting, her philanthropic and social-justice work, and her relationships seem in orbit around the central fact of her life: She is a survivor. And it is her survival of sexual abuse, not the stroke, that is the heart of this book. Although her celebrity is incidental to her account of a woman who finally found a way to tell the truth about what was done to her, what is done to many, if her fame gets that message to more people, including more survivors, then good for celebrity. “I can tell our story because I am unafraid to say it is our story. … and we are ready to sing a new story, and this now is how I am going to sing it. By telling you this.”

Instructions for fellow survivors

Most of what Stone has to teach is in the telling of that story, but in a few places she resorts to overt instruction for fellow survivors of abuse: get help, get the facts on the record, store the record in a safe place. “If it has to be, let this be the one lesson you take away from my life and experiences,” she says.

This is a well-written, insightful memoir and its stars, commanding equal billing, are grit and compassion.

Theresa Forsman is a longtime member of the Ethical Culture Society of Bergen County.