By Curt Collier

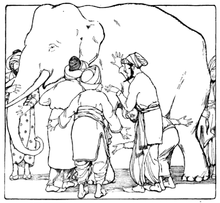

The ancient, and oft repeated, parable of the Blind Men and the Elephant comes to us from the Indian subcontinent. In this 3,000-year-old tale, an elephant is brought into a village and five men, all blind, go to check it out. As the story goes, each feels only one part of the elephant, the trunk, the ear, the side, the leg, and the tail, and then each concludes, from his limited experience, what indeed an elephant is, as none had ever seen one. Conflicts arise, due to their limited experience with the totality of the beast, as each description is radically different from that of the others. For example, one feeling the leg says that an elephant is like a palm tree, whereas another, feeling the side, concludes an elephant is like a wall, and so on. Their disagreement comes to blows as each clings to his beliefs and doubts the experiences of others. The moral of the story, at least to modern readers, is that the men failed to grasp that perhaps what they were encountering is vastly larger than their individual experiences, and rather than doubt the perceptions of others, they should have worked together to construct a larger truth.

Improving moral reasoning

One of the most difficult concepts to grasp in Felix Adler’s own writing is his notion of “organicity,” which, despite arising from far different sources than the Indian folktale, arrives at a similar conclusion. Adler expanded on a concept developed by the Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant, who believed that the reality “out there” is impossible to grasp firsthand, and is known to us only by sensations. Kant believed we make sense of reality because our brain is hardwired to process sensory impressions through “categories” in our mind. As we are capable of interpreting moral experiences, as well, Kant thought our mind must be prewired to know what is ethical, and thus all that is needed is to cultivate this part of our brain to improve moral reasoning.

Adler, too, believed each of us has the capacity for moral reasoning, but where he differed from Kant is that one person working alone couldn’t reason themselves to the totality of ethical possibilities (what he called the ethical manifold), as what he thought of as “ethical” was always something larger than could be experienced by one person living at one time. Our goal, for Adler, was for each of us to engage in the stuff of life, and then to come together to share our insights. While this may lead to different interpretations, we are to enter into this dialogue in such a way to discern that a larger vision lay between us. The Society’s platform, for example, was one of the places were individuals, reflecting deeply on their own experience, could share their insights.

Creating a culture of inclusivity

The first challenge Adler realized is that not all are sitting in the room. If only three of the people who “touched the elephant” are able or allowed to share their ideas, we’d not have a complete picture (and therefor a ridiculous understanding of what constitutes an elephant). Our first act, Adler argued, was to be inclusive and to create a culture of inclusivity, and to work to remove the barriers that stopped all voices from sharing. He worked to build schools, advance civil rights, provide health care, and abolish child labor as a way of creating avenues for all to participate in the grand conversation. For us living today, we can think how voices from formerly oppressed or marginalized communities need to be continually uplifted, and to continue to combat those forces, such as racial extremism, that try to limit who is allowed to be heard. But Adler also realized the difficulty we each have in giving voice to our deepest ethical insights. His solution was to act in our relationships to elicit these unique insights (which he called “the best”) from others. For Adler, then, ethics emerges from a communal and a relational process, and in my opinion, this was a brilliant approach.

Adler’s approach provides us with one method for quickly discerning what our actions should be. Actions that bring us in closer dialogue to one another, that allow for the free expression of unique individuals, that remove the fetters that stop voices from being heard, and which deepens relationships and reciprocity should be favored over those that exclude, silence, or demand conformity. As an Ethical Biocentrist, I also seek those processes that allow the rest of being to participate, as well. I further believe that ethics is less something we “find” than a place we “build,” but believe that Adler’s approach is especially valuable in a world of ideas and experiences. It’s why I’m here. It’s what I do.

Curt Collier is interim leader of the Ethical Culture Society of Bergen County.