By Curt Collier

I hate modern dance. Or at least that’s what I used to think. My drama teacher in high school, Miss Downs, was a fan of Martha Graham and she occasionally showed us films of Graham’s work. Snore. That all changed when, in 1999, a year after I moved to New York City, a friend invited a few of us to watch Paul Taylor’s Dance Company perform in Manhattan. I was pleased to find out that most dance performances have several intermissions, which are perfect for grabbing gin and tonics, and I thought this would be a great way to make it through the show. But as I slowly slipped into inebriation, I actually began to watch what was happening on stage. Perhaps it was the incredible choreography –or perhaps it was the Tanqueray–but something shifted within me during that performance.

It was hard to put my finger on it. Modern dance has many admirers, but probably an equal if not a greater number of detractors. It’s seeming fluidity, rarefied movements, and unadorned spectacle is hard for many to get in to. But for some reason I became entranced. Luckily, I was in this incredible place called New York City, where opportunities to see modern dance abound. Shortly after watching Taylor’s company, I had the opportunity to attend an Alvin Ailey Dance Company performance (loved it) and then some amazing dancers at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery. What was it that was so fascinating? Why was it getting increasingly difficult to take my eyes off the stage?

Shinto ritual makes way for the divine

When you study Japanese Shinto ritual, a common theme sets it apart from Western religious practices. The Shintoists believe that humans, born pure and clean, get tainted by the everyday circumstances of our lives. Impure food, impure thoughts, superfluous distractions, the give-and-take of business dealings, etc., all dampen our ability to shine. One author described this concept using the metaphor of dust falling on a mirror. The purpose of Shinto ritual was to brush off these “impurities” so that our inner selves can better reflect the light of the world around us. Unlike the notion of original sin, Shinto states that all of us have a bit of the divine, but that this just needed polishing up now and then. The question is, by what process should this occur?

This is challenging, for what is unique to Shinto is also the belief that each human possesses the ability to “dust themselves off,” and no priest or intermediary is actually needed (if but to assist). Developed over thousands of years, the Shinto process to remove impurity is to engage in pure movement, thought, or action and this focused activity has the desired cleansing effect. Shinto rituals are highly proscribed, so complicated, in fact, that often a guide is needed to assist with the process, but anyone can learn them on their own. They encourage that doing calligraphy, shooting an arrow, or drinking tea can all be opportunities for this process. Proceeding through an exact and precise ritualized action of these activities, we realign ourselves and come out on the other end cleansed.

Transformation through ritual

If you’ve not been to Japan, Japanese forms of Zen Buddhism share a similar aesthetic with Shinto ritual, and if you’ve ever observed a Japanese Tea Ceremony, you’ll understand what I’m talking about. The tea ritual is highly formalized, with several important steps that can take time to fully master. The setting of the table, the particulars of the equipment used, even the design of the room where the tea ritual takes place all contribute to the precision of the ceremony. As with Shinto rituals, the more one aligns oneself with pure thought and motion, the more likely one is to be transformed by these practices.

I think perhaps that is what intrigued me with modern dance. Despite what appears to be haphazard motions, there is a deep structure and grammar to the dance. Something with precision begins to emerge from what at first glance appears to be nothing more than chaos. And that precise thing is beautiful to behold even if difficult to describe.

A whirl of movement, but with a purpose

I am a messy person and I revel in chaotic spaces. I live life surrounded by piles of ongoing projects, paint spills, scraps of notes, and bits and pieces of performative creative expression. Some of you share that predilection; others would drown in such a space. While some love the freedom of disorder, others get lost in disarray. Vive la différence. But I think there is something very different between true untidiness and creative clutter, for lack of a better analogy, and each of us should find the limit separating tidiness and barren sterility. Our lives should be more like modern dance, a whirl of movement and energy (with more than a splash of color), but also purposeful enough that something virtuous is given birth to during this process. A clarity of thought, action, and deed can dust off the accretion of world-weariness and does allow something fresh and beautiful to emerge.

For me, the ritual of creative, innovative action, purposefully guided and with clear intent, can be a transformative spiritual practice. I know because through this dance, beauty and virtue have emerged, and these experiences have been transformative and allowed for fresh perspective. Viewed from afar, these actions may appear clunky and graceless, but the closer one gets to the swirl, the more one realizes there is indeed a grammar: the affirmation of worth of the other, the inclusive collaborative spirit, the expressions of care, and honoring commitments have their own precision, even if we don’t always recognize them as being so.

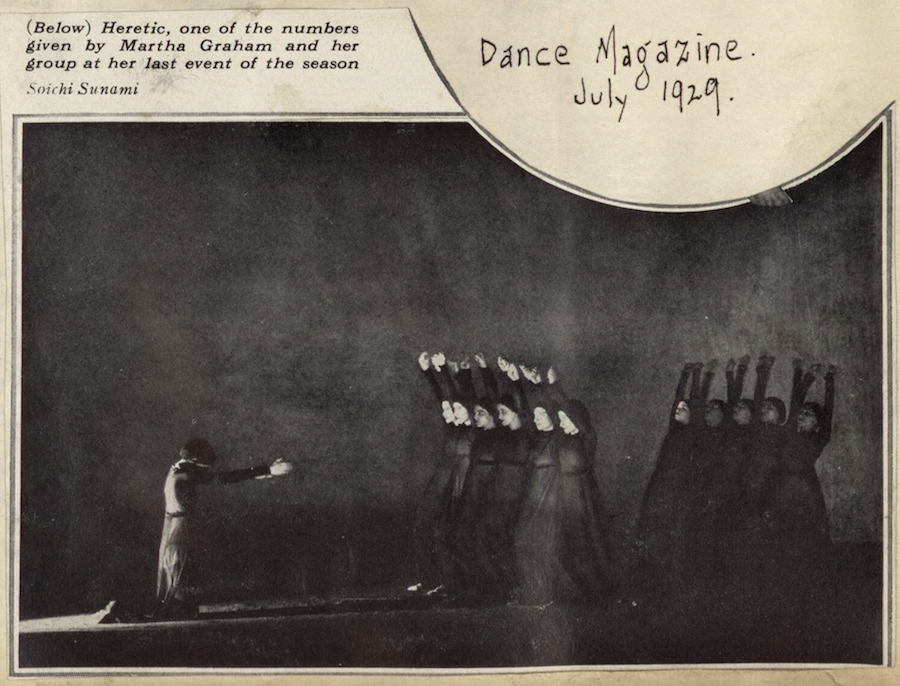

I’d like to hear your thoughts on this. Through what process do you “realign” yourself with the universe–and is that really even needed? In the meantime, grab a cup of spiced tea, exactly one slice of lemon cut into 1/8th wedges, and Google Martha Graham’s 1929 recording of “Heretic.” And call me in the morning.

Curt Collier is leader of the Ethical Culture Society of Bergen County.