By Dr. Joseph Chuman

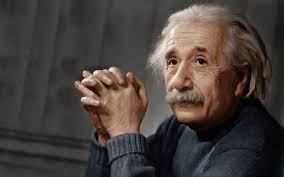

The inspiration for my address this morning was a news feature that appeared early last month and made quite a buzz in certain intellectual circles. The issue at hand was the auctioning by Christie’s of a brief letter written by Albert Einstein in 1954, a year before his death. The letter was written to a German philosopher by the name of Eric Gutkind in response to a book Gutkind had written called “Choose Life: The Biblical Call to Revolt” that, apparently, Einstein did not much like. According to an article in the New York Times, the book “presented the Bible as a call to arms, and Judaism and Israel as incorruptible.” Einstein used his letter to Gutkind to very briefly express his opinions on God, the Bible, Judaism, and his relation to the Jewish people.

The letter was purchased by an anonymous bidder, who paid the astounding amount of almost $2.9 million for a missive that was barely a page and a half long. The sale of this letter superseded the amount paid for the much more significant note that Einstein had sent to President Franklin Roosevelt in 1939 that warned of “the possibility of the creation of extremely powerful bombs,” and served as the catalyst for the research that led to the creation of the Manhattan Project. That letter was sold by Christie’s in 2002 for the mere sum of $2.1 million.

I suspect that the value of what had come to be called Einstein’s “God Letter” is a testament to the influence of celebrity and to the fact that there are lots of people with lots of money to spend on these kinds of things. What may also have influenced the price is the contemporary relevance of the letter’s view on religion.

We live in an age of religious polemics, wherein the influence of fundamentalist religion remains very strong, while on the other end of the spectrum, we have the so-called “New Atheists” as well as about 35 percent of millennials claiming to have “no religion.” In his letter, Einstein, who was the scientific rock star of the 20th century, did not equivocate with regard to his feelings about aspects of religion for which he had no use. He directly proclaimed, “The word God is for me nothing but the expression of and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of venerable but still rather primitive legends,” and, “No interpretation, no matter how subtle, can (for me) change anything about this.”

But I still remained surprised at the significance paid to this letter in that there is nothing that Einstein says in it that he hadn’t said many times before, in fact, throughout the entirety of his adult life. And it is the content of his views on religion that is the mainstay of my address this morning, content that I think should be of great interest to us as Ethical Culturists.

Einstein’s views directly relevant to Ethical Culture

First, let me explain why I think Einstein’s views on religion are directly relevant to us.

Since it was founded in 1876, Ethical Culture has left its followers with a burden that continually confuses outsiders and irks many of its members, as well. What I am referring to is the fact that Ethical Culture considers itself to be a religion, yet it does not proclaim a belief in a Supreme Being. Without God at the center, it leaves a lot of people scratching their heads in what sense Ethical Culture can be religious at all. For those people to whom religion is a prevailingly negative concept, Ethical Culture’s self-identification as a religion is barely tolerated and perhaps with some discomfort. For those who do embrace Ethical Culture’s character as religious, such folks are still left with a lot of explaining to do in defending what does not in the minds of most people seem obvious at all. In simplest terms, it boils down to the question, how can you consider yourself a religion if you don’t affirm a belief in God?

Yet, if we look at Ethical Culture’s origins, there can be little doubt that its founder, Felix Adler, took religion very seriously and thought that in creating Ethical Culture he was doing something religious. Ethical Culture was the product of several major intellectual currents in the 19th century that flowed together to create it. To put it in briefest terms, science in the 19th century had severely whittled away and destroyed many of the major truth claims of religion. Scientific criticism of the Bible, archeology, geology, astronomy, biology, and especially evolution had made it increasingly impossible for educated people to believe in miracles, in the biblical accounts of creation, and in a personal God who intervenes in human affairs and who punishes the wicked and rewards the righteous. And yet, while science destroyed many religious beliefs about the world, it couldn’t totally do away with the religious spirit.

The great German philosopher Immanuel Kant had powerfully argued that all we can know are those things that we can experience. And realities that transcend the world of our sense experience, among them God, we cannot know. But some of Kant’s followers believed that we can get to know these transcendental realities, not through our reason or science or through our normal experience but by means of our intuition and our feelings. Such thinkers became known as romantics, and they had great influence in literature, art, philosophy, and religion.

One of the great American thinkers, who was an exponent of this romantic tradition, was the sage Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson did not believe in supernaturalism or a personal God or in miracles. But he did believe in an all-encompassing, impersonal spirit that pervades all things, including us. We can sense this spiritual reality when walking through the woods and imbibing the grandeur of nature. We can sense it in the loftiest ideals of truth, beauty. and justice, and we can sense it in the loftiest aspirations of men and women that elevate us. There is the world we apprehend with our senses, but this romantic sensibility imbues us with the feeling that there is something beyond it all; that there is something “more” to reality than the world that preoccupies us, however indefinable this something “more” may be.

Through our senses, we know of a reality beyond the material world

It is this sensibility of a reality beyond the material world that we know through the regular use of our senses and is dispensed to us through the employment of science, a realm that is spiritual, august, sublime, yet impersonal, a realm that Emerson and those like him referred to as spiritual or religious.

Felix Adler was greatly influenced by Emerson and broadly shared Emerson’s sensibility about religion and the religious. Felix Adler once described Ethical Culture by proclaiming that it is “ultra-scientific without being anti-scientific.” In other words, he accepted the scientific world-view, but believed that there is a wider reality beyond the reality that science uncovers for us. But, again, this wider reality is not supernatural or personal, or has anything to do whatsoever with the creeds, doctrines, and myths associated with historical religions such as Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and so forth. It is a generic, universal religious sensibility, so to speak, and is and is not exclusively identified with any specific, historic religion, although the traditional religions may express or be inspired by elements of it.

While he had his own specific take on it, Einstein’s religion and sense of the religious falls into this general sense of religious appreciation. And it was this appreciation of religion that places Einstein very close to us and led him to appreciate Ethical Culture, not merely for our achievements in the arena of social justice, but for what Ethical Culture essentially is and religiously stands for.

Einstein did not merely know Ethical Culture from a distance. Before World War I, Ethical Culture was an international movement with societies and fellowships in Britain, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and elsewhere. When, in the first decade of the 20th century, Einstein was working in a patent office in Bern, Switzerland, where he was formulating the theory of relativity, he would on occasion attend meetings of an Ethical Culture fellowship in the city of Bern. Almost 50 years later in a very laudatory letter, Einstein praised not only the work of Ethical Culture, but our underlying sensibilities in a way that I personally believe gets us exactly right. I will get to that statement toward the end of my address. But first, some discussion of what lies in between.

Albert Einstein was born in the city of Ulm, Germany, on March 14, 1879, into a family of assimilated German Jews. His first formal education started at the age of 6 in a Catholic primary school in Munich, where the family moved about year after his birth. His family also had him privately tutored in the principles of Judaism as a counterweight to the Catholic teaching he was receiving at school. It was at public school at age 7 that the young Einstein, the only Jewish student in his class, had his first encounter with ant-Semitism. It was shortly after this that Einstein was introduced to scientific texts, which led him to an absolute abandonment of both the Christian and Judaic principles he had been taught.

His introduction to science was a type of awakening that, by his own admission, led to a suspicion of every kind of authority and deep sense of skepticism about received values in general. Anti-authoritarianism was deeply rooted in Einstein’s character He hated militarism, he didn’t like parades, and as was well known he was very visibly non-conformist when it came to his personal attire. Having fled the horrors of Nazism, Einstein was a humanitarian and internationalist who once said, “Nationalism is an infantile sickness. It is the measles of the human race.” And he rebelled against the dictates of received religion. No doubt his anti-authoritarianism was linked to his extraordinary and unique scientific genius and creativity. But there were other sources of that scientific creativity, which we will get to in a little while.

Einstein never attended religious services

His rejection of Judaic principles was manifest, among other ways, in his refusal to have a bar mitzvah, in his marrying a woman who was Greek Orthodox, and at the end of his life, choosing to be cremated, contrary to Jewish religious doctrine. As far as is known, Einstein never attended religious services and only attended a synagogue for social events.

His rejection of traditional religion presents the first horn of what on its face strikes one as a contradiction, which can only be resolved through an understanding of Einstein’s specific interpretation and understanding of religion.

On the one hand, he powerfully, indeed, at times militantly, rejected the manifestations of traditional religion, Jewish, Christian, and otherwise. This included the rejection of religious myths, doctrine, an afterlife, and most especially any belief in a supernatural God, a God who is personal, judges us or in any sense enters into the world through revelation, doctrines proclaimed through sacred scriptures, or through miracles. He at times was acerbic in his condemnation of supernaturalist religion, with a vigor that would warm the heart of a militant New Atheist. In fact, Richard Dawkins was an unsuccessful bidder for Einstein’s “God letter.” Not untypical was the following, quoted from his obituary in the New York Times on April 19, 1955: “I cannot imagine a God who rewards and punishes the objects of his creation, whose purposes are modeled after our own—a God, in short, who is but a reflection of human frailty. Neither can I believe that an individual survives the death of his body, although feeble souls harbor such thoughts through fear or ridiculous egotisms.” That’s pretty strong stuff.

At the same time, Einstein, proclaimed, with equal conviction, that he was a very religious person, and that he was not an atheist, agnostic or even a freethinker. When it comes to his position on atheism, the contemporary militant or New Atheist will derive no support or comfort from Einstein. In fact, he could be as caustic in his criticism of atheists as he was of orthodox believers. He declared “…there are people who say there is no God. But what really makes me angry is that they quote me for support of such views.”

Then, in an address given in 1941, Einstein elaborated:

“I was barked at by numerous dogs who are earning their food guarding ignorance and superstition for the benefit of those who profit from it. Then there are the fanatical atheists whose intolerance is of the same kind as the intolerance of the religious fanatics and comes from the same source. They are like slaves who are still feeling the weight of their chains, which they have thrown off after hard struggle. They are creatures who—in their grudge against the traditional ‘opium for the people’—cannot bear the music of the spheres. The Wonder of nature does not become smaller because one cannot measure it by the standards of human morals and human aims.”

That last sentence, referencing the “Wonder of nature,” opens the door to Einstein’s views on God and religion.

The great scientist spoke often of religion

In order to unravel this ostensible contradiction, one has to look into what Einstein meant by God, and in what sense he was religious. It should be said at the start that Einstein took his religious views very seriously and spoke and wrote about religion throughout his life in private conversations, in correspondences, in written essays, and at public meetings. In fact, as implied, he often asserted that his religious sensibilities were a necessary source of his scientific insights.

When asked about his views on God, Einstein frequently and somewhat cagily, responded that he believed in the God of Spinoza. In order to know what that means, one needs to know the nature of Spinoza’s God.

Baruch Spinoza was a 17th century Dutch/Jewish philosopher who was a rationalist and flourished in the Age of Science and was an early figure in the European Enlightenment. In his philosophy, Spinoza was 100, if not 200, years ahead of his time and in many ways helped to create the modern world.

From a religious perspective, Spinoza’s views were totally heretical. As is well known, he was excommunicated from the Amsterdam Jewish community, while never converting to Christianity.

Jewish and Christian theology is based on the premise that reality is comprised of two separate substances. There is spirit and there is matter. Or, we might say there is God and there is nature. In his masterpiece, The Ethics, which is written in the form of geometry axioms, postulates, and theorems, Spinoza was able to demonstrate that there are not two substances, but simply one substance. Reality is not divided into God and Nature. But God and Nature are one and the same. God is not supernatural or above or outside of Nature. God is Nature.

But if God is Nature, then Spinoza’s God is almost nothing like the God of Judaism, Christianity, and, for that matter, Islam. If God is Nature, then Spinoza’s God is austerely and totally impersonal. If God is Nature, then God is not a creator, and in Spinoza’s view Nature is self-created, so to speak. Spinoza’s God has no will. If Spinoza’s God has a “will,” then there is no intentionality to it. It is simply the way Nature behaves, or we might say is manifested in the laws of Nature. Spinoza’s God has no ethical properties, and what we humans consider to be good or evil is, therefore, simply relative to human interests. Spinoza’s God, needless to say, does not reward or punish humans for their behavior, and Spinoza’s God is not one whom one would pray to.

But most important for Einstein is Nature according to Spinoza—and here we can see the influence of Newtonian science. Nature behaves according to laws and reasons that are completely deterministic. To state it in the broadest terms, Nature or God is an infinitely vast and wondrous system and concatenation of causes and effects for which there are no exceptions whatsoever. Every action, everything that occurs, occurs as a result of causes that are rationally conjoined to each other. So everything occurs out of necessity, and there is no freedom, there are no accidents, in Spinoza’s view of reality, nor in Einstein’s. If things seem to happen by accident or for no ostensible reason, it is not because they do. We just assume that they do, but because we are ignorant, because our knowledge, our reason, and science have not penetrated far enough for us to understand the way in which phenomena are the product of ulterior causes. For Spinoza and for Einstein, this determinism pertains to human thought, feelings, and actions, for as Spinoza has made clear, we are simply natural beings who are part of Nature, and have no special status outside of Nature as the traditional religions maintain.

Manifestation of the divine is only partially comprehensible

For Einstein, this vast, indeed, infinite system of causes and effects that make up the universe was the wellspring of powerful religious feelings and a source of inspiration. For Einstein, knowledge of God can be obtained by observing the visible processes of Nature, but with the proviso that the manifestation of the divine in the universe is only partially comprehensible to the human intellect.

For Einstein, reality is a huge rational system, which through the use of our own reason and science we can get to know. But we can know only a very small part of it. Beyond what we can know lies the vast unknown, which gives rise to a sense of mystery, which Einstein construed as sublime and inspiring. But behind it all is all-encompassing Reason, which he identified with God. He even went so far as to say “everyone who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the Universe—a spirit vastly superior to that of man, and one in the face of which we with our modest powers must feel humble.” To put it in simpler terms, he said, “My views are near to those of Spinoza: admiration for the beauty of and belief in the logical simplicity of the order and harmony which we can grasp humbly and only imperfectly.”

Einstein often referred to his views as “cosmic religion,” which gives rise to cosmic religious feelings, which are akin to feelings of awe. Einstein had once said:

“The most beautiful experience we can have is of the mysterious…A knowledge of the existence of something we cannot penetrate, our perceptions of the profoundest reason and the most radiant beauty, which only in their most primitive forms are accessible to our minds—it is this knowledge and this emotion that constitutes true religiosity; in this sense, and in this alone, I am a deeply religious man. “

Thought and nature reveal ‘marvelous order’

Cosmic religious feelings also give rise, as he put it, to recognition of the “futility of human desires and the sublimity and marvelous order which reveals itself both in nature and in the world of thought.”

But these feelings, for Einstein, were not mere window dressing, by any means. Einstein fervently believed that an apprehension of the mysterious, of awe and the belief that behind or within reality there exists an order that is rationally structured and is scrutable to the human mind, even very partially, is what impels and inspires scientific discovery. Speaking about his profession, he said:

“…science can only be created by those who are thoroughly imbued with the aspiration toward truth and understanding. This source of feeling, however, springs from the sphere of religion…I cannot conceive of the genuine scientist without that profound faith. The situation may be expressed by an image: science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.”

Science without religion is lame, because scientific discovery requires this faith in the rational structure of reality inspired by a sense of mystery and awe. And religion without science is blind because religion, as Einstein understands it, emanates from a cosmic appreciation of nature that science progressively reveals.

Let me close by saying that when it came to ethics, despite his philosophical determinism, human beings must act as if they are free. For Einstein, ethical behavior should be based on sympathy, education, and social ties and needs. In his view, our moral conduct on which he placed great emphasis is nevertheless independent of both religion and science. He was among these thinkers who believed that science can tell us what is, but it cannot tell us how we ought to behave.

And speaking of ethics, this would be a good time to end by invoking Albert Einstein’s letter to the New York Ethical Society, written in January 1951, congratulating Ethical Culture on its 75th anniversary. If truth be told, the motivation to write the letter came as an invitation from Algernon Black, a famed leader of the New York Society. I like this missive, not only because Einstein was extremely laudatory of Ethical Culture, but because it expresses—I think very correctly—what lies at the heart of Ethical Culture and the emotional basis of ethics, which was close to his own thinking. So let me end by reading that letter, which maybe if anyone can find it, we can auction off for at least $5 million.

Letter from Einstein to New York Ethical Society

“I feel the need of sending my congratulations and good wishes to your Ethical Culture Society on the occasion of its anniversary celebration. True, this is not a time when we can regard with satisfaction the results which honest striving on the ethical plane has achieved in these 75 years. For one can hardly assert that the moral aspect of human life in general is today more satisfactory than it was in 1876.

“At that time the view obtained that everything was to be hoped for from enlightenment in the field of ascertainable scientific fact and the conquest of prejudice and superstition. All this is of course important and worthy of the best efforts of the finest people. And in this regard much has been accomplished in these seventy-five years and has been disseminated by means of literature and the stage. But the clearing away of obstacles does not by itself lead to an ennoblement of social and individual life. For along with this negative result a positive aspiration and effort for an ethical-moral configuration of our common life is of overriding importance. Here, no science can save us. I believe, indeed, that overemphasis on the purely intellectual attitude, often directed solely to the practical and factual, in our education, has led directly to impairment of our ethical values. I am not thinking so much of the dangers with which technical progress has directly confronted mankind, as of the stifling of mutual human considerations by a “matter-of-fact” habit of thought that has come to lie like a killing frost upon human relations.

“Fulfillment on the moral and aesthetic side is a goal which lies closer to the preoccupations of art than it does to those of science. Of course, understanding of our fellow-beings is important. But this understanding becomes fruitful only when it is sustained by sympathetic feeling in joy and in sorrow. The cultivation of this most important spring of moral action is that which is left of religion when it has been purified of the elements of superstition. In this sense, religion forms an important part of education, where it receives far too little consideration, and that little not sufficiently systematic.

“The frightful dilemma of the political world situation has much to do with this sin on the part of our civilization. Without “ethical culture” there is no salvation for humanity.”

Dr. Joseph Chuman, leader of the Ethical Culture Society of Bergen County, delivered this platform address on Jan. 6, 2019.