By Curt Collier

It was nearing the end of another amazing summer. I have the enviable job of spending each July and August in three of the most beautiful parks in the nation: Glacier, Grand Teton, and Yellowstone National Park. When not serving as the interim leader of the Ethical Culture Society of Bergen County, I am the National Youth Programs Director for an environmental nonprofit created by the National Park Service. Each summer, I run a corps-styled program with 100 young adults I gather from across the nation working on service projects benefitting the parks. It is a lot of work, a lot of hiking carrying tools, a lot of nights sleeping in tents, and some of the most wonderful times imaginable.

At the end of this season I had pre-arranged to bring three young men back to New York in my truck, a sort of great American road trip to see sights and extend our vacation. After leaving Yellowstone we camped beside Devil’s Tower National Monument and that night watched “Close Encounters,” which features the geologic formation, on my computer. The movie was exciting for me as a youth…. they just found it boring. They found Badlands National Park far more fun, as you can literally run anywhere and the stars at night are amazing. But one stop had them confused.

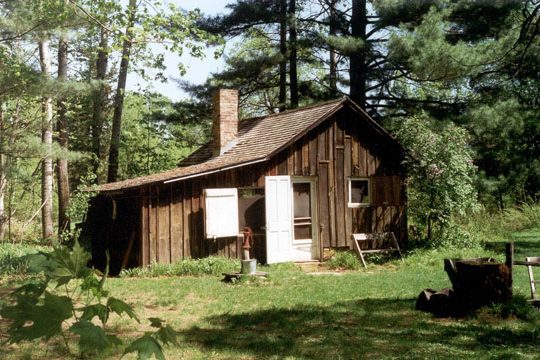

“What are we doing in these woods Mr. Collier? I don’t think this is a place for Black folk!” one youth jokingly but nervously blurted. “It’s OK, we’re allowed to be here,” I said. “I just want to show you an amazing place.” We hiked along the dirt road through a thicket of trees and restored prairie grass just outside Baraboo, Wisconsin. “What is this place?” another pushed more earnestly. “Just a little further” I said calmly. And finally, around the bend it appeared–a small cabin in the woods. “This is it,” I said proudly. “THIS….this is what?” one asked. I pulled out my copy of “A Sand County Almanac” from my daypack and turned to the page in the book showing Aldo Leopold sitting before this very cabin. I presented it as a big reveal and waited. “Who is that?” the jokester asked, unimpressed. (Geez, I thought to myself. I’ve only talked about the book like a hundred times). One youth, a nature-loving Dominican named Andy, turned to me and asked, “Is this really where he wrote that book?” “It is indeed,” I said. He knew the book as I had given it to him as a gift before he left to work that summer in Yellowstone.

I told the others that Aldo Leopold was one of the most notable naturalists in the history of America. It was he, a former wolf-killing forester turned conservationist and professor, who wrote the book before them. The book is mostly a collection of stories related to his activities on the farm and surrounding county. But the last chapter, “The Land Ethic,” lays out a new vision for conservation, one that places humans as part of a community, not its crowning achievement. He wrote, “We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” For many indigenous communities around the world, this was no great revelation. But for Leopold’s white audience in 1949, the book inspired a revolution in conservation ethics.

A new ethic that includes nature

The central principle of the book is that we need a new ethic, one that includes nature. He lamented that Americans had destroyed wetlands, plowed under prairies, dammed rivers, and let tons of life-giving topsoil dry up and blow away without batting an eye. It was time, he argued, for a new ethic where people were ashamed of these events, much as we feel shame when cheating on a loved one or bringing harm to a friend. The basis of his ethics was simple and straightforward. He wrote “a thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

Despite the philosophical challenges of this statement (a form of rule consequentialism if you’re into such academic exactness), I love its down-to-earth elegance. I’m also heartened by the fact that he included beauty as a resultant of proper action.

The one thing Leopold did not include in his book, the thing that haunts all ethical systems, is a basis for motivation. Why should we even care? Perhaps the previous chapters and their colorful visions of life on a small Midwestern plot of land in a vast green space were intended to bring forth feelings of longing that run deep in our animal being. If only that were enough. Unfortunately, however, no philosophical tradition, not even biocentrism, can save us if we simply don’t care. “Aye, there’s the rub,” as Hamlet lamented.

In relationship, something unique can emerge

A solution to this conundrum is hard to find and most unimaginative approaches commonly try shaming, invoking fear, enticing with rewards, or compelling. I’m not interested in any of that. I am, however, reminded of the relational emphasis within Ethical Culture’s ethic. Sometimes in our ordinary everyday experiences with another, something unique happens; a relationship develops. And in that space, something unique can indeed emerge, a feeling really, that creeps up slowly, but can grasp our heart firmly; a caring disposition towards that other. You can imagine, then, my desire to build connections between people and green, healthy spaces. Not to shame them into recycling their cans, cajoling them to pick paper over plastic by pointing to pictures of plastic choking sea turtles, invoking night-terrors of climate change, nor even trying to entice them with the simple fact that livable spaces prolong lives and line our pockets. It starts far simpler than that, as all meaningful relationships do.

I have much more to say about the topic, but will end it there. The amazing power of healthy relationships is their ability to transform lives, to build lives, in fact. In reciprocal relationships, we find the energy to go to work, to make hard choices for the good of others above ourselves, to have adult conversations, and to try again and again each morning to make it all happen. I believe Ethical Culture gets this right, and I want to tell you so much more about that. Another day perhaps? Oh, and the young man to whom I gave a copy of “A Sand County Almanac”? He’s now in college studying geography and wants to work on green urban planning. He is also now my adopted son. That’s the power of relationships. That’s motivation enough for me to work each and every day for a greener future.

Curt Collier is interim leader of the Ethical Culture Society of Bergen County.